-

![[image]](https://www.balancer.ru/cache/sites/ru/ad/adme/files3/files/news/part_77/776010/128x128-crop/8.jpg)

Флуд и флейм без всякой темы

потому что Balancer против сноса всего в мусорТеги:

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Гидрометеорология, природно-климатические условия.

Хренассе... Добросовестно прочитал всю тему. Проникся. Пишите ещё. Не сдерживайте себя.

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Скорбная весть.

Черномор™> Бред.

Наши в училище, на кафедре, говорят, что не бред. Опять же спорить не буду, не та это тема((((((

Наши в училище, на кафедре, говорят, что не бред. Опять же спорить не буду, не та это тема((((((

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Флот в операции ZZ.Z.ZZ на Украине.

sahureka>>> два проекта 775 причастные к взрывам в порту Бердянска, спутниковые фото показаны в автономном плавании в сторону Севастополя, у вас есть новости, если они уже в порту?

Andru> sahureka>> https://i.ibb.co/vXmspn1/FOs9-Hcz-XEAQm5y-J.jpg

J.B.>> Но не могу не сказать, что Le ragazze italiane sono le più belle

Andru> Chelentano..

У меня прекрасные воспоминания о поездке в Москву и Ленинград в апреле 1987 года.

как любитель военной истории также музеев Ленинграда и Москвы

вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

Andru> sahureka>> https://i.ibb.co/vXmspn1/FOs9-Hcz-XEAQm5y-J.jpg

J.B.>> Но не могу не сказать, что Le ragazze italiane sono le più belle

Andru> Chelentano..

У меня прекрасные воспоминания о поездке в Москву и Ленинград в апреле 1987 года.

как любитель военной истории также музеев Ленинграда и Москвы

вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

sahureka> вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

- Черномор™ [25.03.2022 21:26]: Перенос сообщений из Скорбная весть

- Черномор™ [25.03.2022 21:29]: Перенос сообщений из Флуд и флейм по спецоперации на Украине

sahureka> У меня прекрасные воспоминания о поездке в Москву и Ленинград в апреле 1987 года.

sahureka> как любитель военной истории также музеев Ленинграда и Москвы

sahureka> вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

С

Скоро сможете за наши рубли объездить всю нашу Великую страну...

sahureka> как любитель военной истории также музеев Ленинграда и Москвы

sahureka> вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

С

Скоро сможете за наши рубли объездить всю нашу Великую страну...

sahureka>> вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

В.Б.> Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

Этого я не знал, это было написано только по-русски и мне было трудно перевести, я был в гостях один, без группы итальянцев в организованном туре и без русского гида, который посещал в это время другие места в Ленинграде .

Для фото попросил помощи у солдата который там был, он любезно принял и не уведомил меня о написанном

Извините, я всегда уважаю места, которые я посетил

В.Б.> Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

Этого я не знал, это было написано только по-русски и мне было трудно перевести, я был в гостях один, без группы итальянцев в организованном туре и без русского гида, который посещал в это время другие места в Ленинграде .

Для фото попросил помощи у солдата который там был, он любезно принял и не уведомил меня о написанном

Извините, я всегда уважаю места, которые я посетил

sahureka>>> вот фото в ленинграде (в то время так называлось)

В.Б.>> Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

sahureka> Извините, я всегда уважаю места, которые я посетил

Да шутка.... Сейчас, кстати, там можно детям ползать почти где угодно (кроме заведомо опасных мест), крутить всё, что крутится, и фотографироваться можно, где хочешь...

Смешно такие надписи читать на броне, как будто "СУ"-шке хуже от этого будет. Не Рембрандт же...

В.Б.>> Там, кстати, надпись как раз около вашей правой руки "Экспонаты не трогать!" (Mostre non toccare!).

sahureka> Извините, я всегда уважаю места, которые я посетил

Да шутка.... Сейчас, кстати, там можно детям ползать почти где угодно (кроме заведомо опасных мест), крутить всё, что крутится, и фотографироваться можно, где хочешь...

Смешно такие надписи читать на броне, как будто "СУ"-шке хуже от этого будет. Не Рембрандт же...

0--ZEvS--0> Заметьте, что технологии дело наживное, а вот природные ресурсы - нет. О, мне надо будет поставить это как подпись.

интересно а нигерийцы тоже так думают

интересно а нигерийцы тоже так думают

0--ZEvS--0>> Заметьте, что технологии дело наживное, а вот природные ресурсы - нет. О, мне надо будет поставить это как подпись.

G.g.> интересно а нигерийцы тоже так думают

Нет, не думают - проводят срочное техническое освидетельствование резервных и выключенных ранее за ненадобностью нефтегазосборных и межпромысловых трубопроводов. То же и Габон и Конго.

G.g.> интересно а нигерийцы тоже так думают

Нет, не думают - проводят срочное техническое освидетельствование резервных и выключенных ранее за ненадобностью нефтегазосборных и межпромысловых трубопроводов. То же и Габон и Конго.

- Черномор™ [26.03.2022 01:52]: Перенос сообщений из Гидрометеорология, природно-климатические условия

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Санкции.

Bornholmer> Сахар есть, расфасованный в Литве, и потому не считающийся белорусским, подозреваю. Но нет соли, соды, подсолнечного масла, еще чего-то, полки пустые... все декоммунизировали

Едем сейчас из Минска. Брат купил блин две пачки соли и две - соды. Дефицит карахо! Пока гнали к границе, впали в тягостное раздумье - вдруг белорусские пограничники решат, что это наркота? Ну, типа, едут два мужика в пустой машине - просто с солью! Не, разобрались бы, конечно, но время потрачено впустую, и нервы вытрепаны. Весь в слезах и матюгах, выбросил соль с содой! Аааааа, ну и дичь! Дожили!

Едем сейчас из Минска. Брат купил блин две пачки соли и две - соды. Дефицит карахо! Пока гнали к границе, впали в тягостное раздумье - вдруг белорусские пограничники решат, что это наркота? Ну, типа, едут два мужика в пустой машине - просто с солью! Не, разобрались бы, конечно, но время потрачено впустую, и нервы вытрепаны. Весь в слезах и матюгах, выбросил соль с содой! Аааааа, ну и дичь! Дожили!

Fakir:

ну мужики, топик про санкции весьма злободневный; предупреждение (+1) по категории «Флуд или офтопик»

Sinus> Открыли бы пограничникам на пробу содержания - все. Они же не дебилы. Вертайтесь взад, подберите..

Где ты был раньше с такой прикольной идеей? Мы уже вверх к морю погнали

Где ты был раньше с такой прикольной идеей? Мы уже вверх к морю погнали

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Спец. операция на Украине.

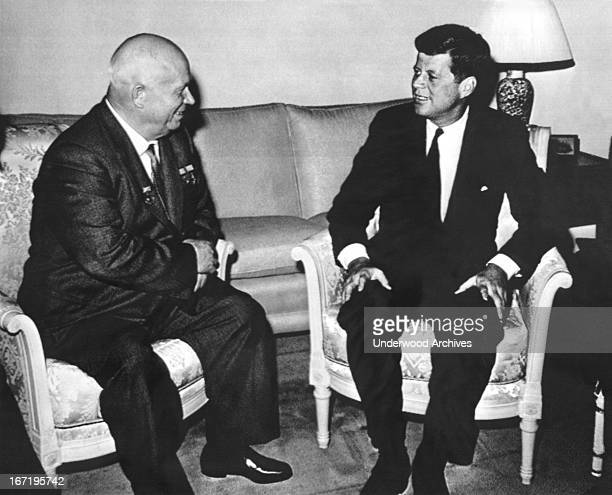

Seafang-45>> Некоторые важные аспекты не обсуждаются, что касается мотивов Хрущева.

NoOrNot> Это, вообще, что такое было?... Похоже на бред в пережку с враньём от Блинкена и Псаки, у которых "совесть" упырей.

Предлагаем вам больше узнать об истории советских времен и истории премьер-министра Хрущева, которая не имеет ничего общего с нынешними лидерами США или России.

NoOrNot> Это, вообще, что такое было?... Похоже на бред в пережку с враньём от Блинкена и Псаки, у которых "совесть" упырей.

Предлагаем вам больше узнать об истории советских времен и истории премьер-министра Хрущева, которая не имеет ничего общего с нынешними лидерами США или России.

Прикреплённые файлы:

Это сообщение редактировалось 26.03.2022 в 20:50

VAS63:

предупреждение (+1) по категории «Флуд или офтопик»

Seafang-45>>> Некоторые важные аспекты не обсуждаются, что касается мотивов Хрущева.

NoOrNot>> Это, вообще, что такое было?... Похоже на бред в пережку с враньём от Блинкена и Псаки, у которых "совесть" упырей.

Seafang-45> Предлагаем вам больше узнать об истории советских времен и истории премьер-министра Хрущева, которая не имеет ничего общего с нынешними лидерами США или России.

NoOrNot>> Это, вообще, что такое было?... Похоже на бред в пережку с враньём от Блинкена и Псаки, у которых "совесть" упырей.

Seafang-45> Предлагаем вам больше узнать об истории советских времен и истории премьер-министра Хрущева, которая не имеет ничего общего с нынешними лидерами США или России.

Прикреплённые файлы:

VAS63:

Не о спецоперации; предупреждение (+1) по категории «Флуд или офтопик»

- VAS [26.03.2022 20:54]: Перенос сообщений из Спец. операция на Украине

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Спец. операция на Украине.

Seafang-45>>> Некоторые важные аспекты не обсуждаются, что касается мотивов Хрущева.

DustyFox> Seafang-45>> Украина объявила о своей независимости от ленинского советского государства в 1920 году..

NoOrNot>> Это, вообще, что такое было?...

DustyFox> Боюсь, это представления американцев о событиях у нас, и о нас. Странно только, что в тексте не наличествует GULAG, samovar, matryoshka, vodka, medved и babalayka.

DustyFox> ПС Хотя нет - GULAG присутствует...

Намеренно исключил вопрос ГУЛАГа из обсуждения, потому что в оригинальном посте не упоминался и был сосредоточен на манифесте премьера Хрущева об Украине, который он знал из своего собственного опыта в качестве первого секретаря в Украине.

DustyFox> Seafang-45>> Украина объявила о своей независимости от ленинского советского государства в 1920 году..

NoOrNot>> Это, вообще, что такое было?...

DustyFox> Боюсь, это представления американцев о событиях у нас, и о нас. Странно только, что в тексте не наличествует GULAG, samovar, matryoshka, vodka, medved и babalayka.

DustyFox> ПС Хотя нет - GULAG присутствует...

Намеренно исключил вопрос ГУЛАГа из обсуждения, потому что в оригинальном посте не упоминался и был сосредоточен на манифесте премьера Хрущева об Украине, который он знал из своего собственного опыта в качестве первого секретаря в Украине.

VAS63:

Не о спецоперации; предупреждение (+1) по категории «Флуд или офтопик»

- VAS [26.03.2022 20:58]: Перенос сообщений из Спец. операция на Украине

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Спец. операция на Украине.

Seafang-45>> Украина объявила о своей независимости от ленинского советского государства в 1920 году - во время русско-польской пограничной войны, но русские войска остановили это движение.

Полл> Это новая, мне не встречавшаяся версия истории России, Украины и СССР.

Полл> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

Лучшие истории наверное вот эти книги:

- Большой террор, сталинская чистка 30-х годов (Роберт Конквест; 1968)

- Дорога к террору (Дж. Арч Гетти и О. В. Наумов (1999; Йельский университет).

Часть книги "Road.." находится на кассете для прослушивания (аудио) на Amazon - если у вас есть доступ.

Мое резюме взято из книги "Большой террор".

Больше, чтобы следовать.

Полл> Это новая, мне не встречавшаяся версия истории России, Украины и СССР.

Полл> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

Лучшие истории наверное вот эти книги:

- Большой террор, сталинская чистка 30-х годов (Роберт Конквест; 1968)

- Дорога к террору (Дж. Арч Гетти и О. В. Наумов (1999; Йельский университет).

Часть книги "Road.." находится на кассете для прослушивания (аудио) на Amazon - если у вас есть доступ.

Мое резюме взято из книги "Большой террор".

Больше, чтобы следовать.

VAS63:

Не о спецоперации; предупреждение (+1) по категории «Флуд или офтопик»

- VAS [26.03.2022 21:10]: Перенос сообщений из Спец. операция на Украине

Сообщение было перенесено из темы Спец. операция на Украине.

Полл> Это новая, мне не встречавшаяся версия истории России, Украины и СССР.

Полл> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

Paul Flewers

Stalin and the Great Terror Politics and Personality in Soviet History

Abstract

This article starts by investigating how the Moscow Trials and the broader Great Terror of the late 1930s were seen outwith the Soviet Union at the time. It then investigates how contemporary and subsequent observers have attempted to explain them, as they viewed them variously as a logical result of Bolshevik theory and practice, rooted in the development of Soviet society, the product of Stalins personal predilections, and an attempt by Stalin to deal with the problems that he faced both personally and politically during the 1930s. It concludes that the staging of the trials and the launching of the terror can be explained by an understanding of both the peculiar nature of the Stalinist socio-economic formation and Stalins particular personal characteristics, and that had Stalin been removed from his post as General Secretary at the Seventeenth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1934, it is extremely unlikely that the Great Terror would have occurred.

Key words Moscow Trials, Stalinism, Soviet Union, state terror.

Note on the author Paul Flewers is a socialist historian and a member of the Editorial Boards of New Interventions and Revolutionary History. His book The New Civili -1941, was recently published by Francis Boutle.

***

Seventy years ago this year, in March 1938, the veteran Bolshevik revolutionaries Nikolai Bukharin, Nikolai Krestinsky, Christian Rakovsky, Aleksei Rykov and Sta r secret police chief Genrikh Yagoda sat with 16 other defendants in Charged with a variety of heinous crimes and having been subjected to months of harsh treatment at the hands of the secret police interrogators, they were harangued by Vyshinsky, found guilty, and sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment, which amounted to the same thing. This was the third of a series of major show trials, the first of which, somewhat ironically, had been held under the auspices of Yagoda. The first was held in August 1936, and resulted in Grigori Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and 14 other Old Bolsheviks being sentenced to death. The second, held in January 1937, resulted in Karl Radek, Yuri Piatakov and 15 others being sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment. Like a three-ring circus, each trial was more flamboyant than its predecessor, with increasingly lurid accusations and confessions about the defendants forming anti-Soviet terrorist groups and for years collaborating with foreign powers and the exiled Trotsky and engaging in terror and sabotage in order to overthrow the Soviet regime and re-establish capitalism, and at the third trial ultimately backdated almost to the October Revolution itself.

These three grotesque show trials were merely the public face of a far deeper

1

and broader reign of repression. In between the second and third trials, in June 1937, the Soviet government announced that several senior military leaders, including Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, had been found guilty of treason, and had been executed. All the while, the Soviet press was providing long lists of names of officials who had been purged for their alleged involvement in heinous activities against the Soviet state, and plenty more were disappearing without notice. The number of people officially executed during 1937-38 stands at 681 692, although this figure has been considered an underestimate, and it has been estimated that during that time squad, physical maltreatment or massive over- 1939, there were 2.9 million prisoners in labour camps and prisons.1 This was the time of the Great Terror.

I: Looking at the Great Terror

At the time, the Moscow Trials and the concurrent reign of terror divided opinion in Britain. The adherents of the pro-Soviet lobby the official communist movement and its fellow-travelling allies reasons for the purges and hailed the show trials as a victory for the socialist state over the forces of counter-revolution,2 or, if they did have a few qualms, very much gave the Soviet regime the benefit of the doubt.3 Some commentators, most notably the left-wing intellectuals Harold Laski and Kingsley Martin, wobbled alarmingly between believ government which were objectively counter- level of repression and lack of free expression in the Soviet Union.4 Some people, whilst unequivocally discounting the allegations and confessions about desiring to return to capitalism, plotting sabotage and collaborating with foreign powers, nonetheless considered that there was a possibility of Trotsky conspiring in a political manner with the defendants with the aim of unseating Stalin, as this was the only way in which opposition to him could be manifested in a country where there was no opportunity for open political discourse.5 There were a few strongly anti- communist observers who accepted the core allegations against the Soviet military leaders, if not all the details,6 presumably on the basis that viewing them as

1. Robert Service, A History Twentieth-Century Russia (London, 1997), pp 222-24.

2. See, for example, Dudley Collard, Soviet Justice and the Trial of Radek and Others (London, 1937); William and Zelda Coates, From Tsardom to the Stalin Constitution (London, 1938); JR Campbell,

Soviet Policy and Its Critics (London, 1939).

3. Sidney and Beatrice Webb accepted the trials as genuine, but with little of the sense of

triumphalism demonstrated by many other pro-Soviet people. Their mammoth treatise accepted that there were considerable restrictions upon independent thinking, and that the powers were dangerously wide, but, all in all, average thoroughly believes that it is to the vigilance of the GPU that is due the continued existence of the Soviet state, which would otherwise have been by internal and external enemies (S and B Webb, Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation (London, 1937), p 586). So alright then.

4. Harold Laski, Record of New Statesman, 30 July 1938, p 192; Kingsley Martin, Moscow New Statesman, 5 September 1936, pp 307-08.

5. John Maynard, on the Trotskyist Political Quarterly, Volume 8, no 3, July 1937, p 94; HC Foxcroft, Revolution Quarterly Review, January 1938, p 9; Peter Horn, Lesson of the Moscow Controversy, March 1937, p 104.

6. Henry Wickham Steed, Anti-Bolshevist Fr International Affairs, Volume 16, no 2, March 1937, p 185; Robert Seton-Watson, Britain and the Dictators: A Survey of Postwar British

2

fraudulent undermined the legitimacy of their call for an Anglo-Soviet bloc against the threat posed by Nazi Germany.

Most observers at the time, however, were horrified by the purges and the trials, and a wide range of commentators in Britain found the accusations and confessions just too fantastic to be taken seriously. The Spectator averred that the evi7 whilst the Economist the third one.8 The veteran socialist Henry Brailsford declared that he had been very sceptical about Soviet justice ever since the Menshevik Trial in 1931, at which it was stated that the Menshevik leader Rafael Abramovich had been plotting in Moscow on the very day when he was actually with Brailsford and other socialists in Brussels.9 It was pointed out that the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen, at which Sedov in 1932, had in fact been demolished in 1917 and not rebuilt.10 EH Carr sarcastically wrote off both DN Pritt, the British apologist for the trials, and the trials 11 Writing pungently about the second trial, but with equal relevance to all three, the academic Goronwy Rees, who until then had held a fairly positive attitude towards the Soviet Union, pointed out that the whole case rested upon confessions lacking documentary evidence, that absurdities, contradictions and even impossibilities in the evidence were not challenged, that exact dates were never given, and that confessions were directed by leading questions. He then asked his erstwhile colleagues of the pro-Soviet lobby if this could be anything other than the justice of a police state.12 George Soloveytchik, a Russian liberal exile, drew out the logic of the trials:

After all, there are only two possibilities: either all these men are guilty, in

build élite which is now being exterminated by its chief is the worst kind of scum the world has yet produced, or else the allegations are not true, and then the indictment of this regime which is compelled to invent such ghastly charges is even more devastating.13

Some people, including George Orwell and the radical novelist Nigel Balchin, found the spectacle of the trials so bizarre that they ridiculed them in a couple of satirical sketches that combined delightful whimsy with devastatingly sharp insights.14

The Stalinists countered their critics, and they did, on the face of it, have a reasonable case. Why, they asked, with the Soviet Union doing so well, would Stalin

Policy (Cambridge, 1938), pp 134-36.

7. of the Spectator, 29 January 1937, pp 153-54.

8. of the Economist, 5 March 1938, p 494.

9. HN Brailsford, New Statesman, 31 July 1937, p 181.

10. Friedrich Adler, The Witchcraft Trial in Moscow (London, 1936), pp 15-16.

11. EH Carr, International Affairs, Volume 16, no 2, March 1937, p 311.

12. Goronwy Rees, Twilight of Spectator, 21 May 1937, p 956.

13. George Soloveytchik, Contemporary Review, February 1938, p 153.

14. George Orwell, New English Weekly, 9 June 1938, p 169; Nigel Balchin,

or Night and Day, 19 August 1937, p 3. article was republished in New Interventions, Volume 11, no 4.

3

stage a series of fake trials, what possible purpose could it have?15 Did not the defendants confess their guilt, unlike Georgi Dimitrov at the Reichstag Fire Trial?16 Observers repelled by the trials racked their brains attempting to comprehend why they had taken place, and why the defendants had confessed. Stalin was considered p.17 Some relied upon clichés, with, for example, the staunch right-winger Charles Petrie proclaiming sagely that the trials proved the adage that revolutions end up devouring their own children,18 an observation that does little to explain the complex issues of power in post-revolutionary societies, whilst a right-wing - 19

The rather obvious point was made that the trials indicated a profound crisis within the Soviet regime.20 But what was behind the crisis? One theory held that Stalin was staging the trials in order to shift the blame for economic mismanagement from his regime onto scapegoats. After outlining many instances of major malfunctions, poor management and general incompetence, the Moscow correspondent of the Economist of gross inefficiency need not cast discredit upon central planning, which, without some such explanation, migh were accepted as genuine by most Soviet citizens, could act as a conductor, using the defendants as a focus for popular discontent that might otherwise be directed against the government.21 CLR James considered that Stalin was attempting to crush a burgeoning wave of opposition.22 He added that Stalin was attempting to pre-empt anyone within the party-state apparatus who intended him to meet the same fate as Robespierre, and that by allowing workers to be promoted into jobs vacated by purged man 23 Many observers, including Winston Churchill and EH Carr, maintained that Stalin was clearing out the Old Bolsheviks who maintained a commitment to the cause of world revolution,24 and others felt that he was purging the bureaucracy in order to reinforce his position by forestalling the rise of any potential opposition, and clearing out all but the most servile of his retinue.25

s denunciation of Stalin in 1956, the

15. Campbell, Soviet Policy and Its Critics, pp 248-49.

16. John Strachey, of the Month: The Soviet Tria Left News, March 1937, 274.

17. of the National Review, July 1937, pp 8-9.

18. Charles Petrie, English Review, October 1936, p 361.

19. of the National Review, April 1938, p 433.

20. of the Wee Economist, 22 August 1936, p 345.

21. Economist, 27 February 1937, p 466.

22. CLR James, World Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International (London, 1937), p

367.

23. CLR James, Controversy, October 1937, p 8.

24. Winston S Churchill, Step by Step, 1936-1939 (London, 1939), pp 60-61; EH Carr, Russia (London,

1937), p 6; at the Contemporary Review, December 1937, pp 690-91; AS Elwell-Sutton, Russian New English Weekly, 12 January 1938, pp 268-89; Franz Borkenau, World Communism: A History of the Communist International (London, 1939), p 423.

25. of the Economist, 25 December 1937, p 634; Nicholas de Basily, Russia Under Soviet Rule: Twenty Years of Bolshevik Experiment (London, 1938), p 252; Frederick Voigt, Unto Caesar (London, 1938), p 253.

4

extensive research work carried out in the West, and the vast array of documentary evidence available for study in the Soviet archives, the Great Terror is accepted as an historical fact. Only a few disturbed individuals, kennelled away in the pro-Stalin corner of the left, now promote an unblemished picture of the Stalin era, or claim that the Moscow Trials represented anything other than a cruel parody of a legal process.26 The extent of the Terror has been extensively researched, although the precise number of victims remains a subject of debate. The cruel methods used by nfessions are public knowledge. The discussion today is largely centred upon questions of interpretation, and the same questions that puzzled observers seven decades ago are often repeated: why did the terror take place, and what were the driving forces behind it?

Many standard accounts of the Terror consider that there were several crucial formative factors. Firstly, there was the emergence of opposition amongst previously trusted members of the Soviet Communist Party leadership during the First Five- w official Maremian Riutin be executed after he was discovered to have written a detailed oppositional programme that called for the removal of Stalin from his post of General Secretary.27 Secondly, there was the implicit snubbing of Stalin at the Seventeenth Party Congress in 1934, where, depend 28 and where there was private talk (which no doubt swiftly reached Stalin) of ary. Thirdly, Kirov was promoting a call for a more liberal party regime, reconciliation with former oppositionists, and a reduction in state coercion.29 Fourthly, there was the subsequent assassination of Kirov on 1 December 1934, for which many commentators claim that Stalin was responsible,30 or that, if there is no direct proof that he was, of which he took full political advantage.31 Ronald Hingley summed up for removing all other rivals, actual and potential, numbering several millions, in the Great Terror of 1937-32

26. Two works demonstrating adage that paper will take anything written on it are Kenneth Cameron, Stalin: Man of Contradiction (Stevenage, 1988), and Harpal Brar, Perestroika: The Complete Collapse of Revisionism (London, 1992), which both consider that the Moscow Trials were fair, and deny the existence of the Ukrainian famine and the Gulag.

27. Ronald Hingley claimed that call to shoot Riutin was to blish a valuable prece and give him right to consign to death without question, let or hindrance, any communist or expelled communist, from the most senior (Ronald Hingley, Joseph Stalin: Man and Legend (London, 1974), p 218).

28. Robert Tucker gave the lower figure, Dmitri Volkogonov the higher one. See Robert Tucker, Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928-1941 (New York, 1992), p 260; Dmitri Volkogonov, Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy (London, 1991), p 200.

29. oris Nicolaevsky, Power and the Soviet Élite (London, 1966), pp 29ff.

30. Particularly Tucker, Stalin in Power, pp 275-76; Robert Conquest, Stalin and the Kirov Murder (London, 1989), passim; Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (Oxford, 1989), p 345.

31. Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (London, 2004), p 315; Donald Rayfield, Stalin and His Henchmen: An Authoritative Portrait of a Tyrant and Those Who Served Him (London, 2004), p 240.

32. Hingley, Joseph Stalin, p 236. Robert Conquest saw the Kirov affair as the on the way to (Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment (London, 1990), p 51).

5

The Great Terror followed the tremendous increase in state coercion and con ctivisation schemes that started in 1929 with the First Five-Year Plan. There had been something of a lull in the level of state repression and official hysteria after the chaotic events of the initial Five-Year Plan had calmed down, and there were widespread hopes that the worst of the upheavals were over. The public image of the Seventeenth Congress was that of party unity having superseded the deep divisions evident at earlier national gatherings. This, however, was very much a false dawn, as a new bout of state- assassi time; indeed, as early as the latter half of 1932.33

ount, the Great Terror itself started with the trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev in August 1936, with many preparatory that the GPU was running four years behind in revealing malcontents, and its head Genrikh Yagoda was replaced by Nikolai Yezhov. The trial of Radek and Piatakov took place in January 1937, and in February-March of that year the Soviet ttee met with the simple agenda of dealing with the matter of Bukharin and Rykov; that is, setting them up for persecution. The centre - Work and Measures for Liquidating Trotskyite and other Double- General Secretary warned that the more successful the Soviet Union became, the enemies; and that members of the Soviet Communist Party were most lax in their appreciation of the dangers posed to the Soviet Union.34 It was a clear signal for the implementation of widespread terror, and by mid-1937, with a purge of the secret police, Stalin was in full control of the machinery of mass repression.35

The period from mid-1937 to late 1938, the Yezhovshchina, was the full-blown Terror, marked most publicly by the grotesque third Moscow Trial in March 1938. The Terror affected practically every corner of the Soviet regime. The middle cadre, by then mostly loyal to the general Stalinist line, was purged, often with the lower echelons whipping up a witch-hunt atmosphere against them. The military leadership and industrial management structures were particularly badly hit, as were party leaderships in the non-Russian republics, but no government department escaped, and soon nobody at all was safe as the dragnet descended to the rank-and-file worker and peasant. Brutal interrogation resulted in those arrested implicating others, some people denounced others for personal revenge or in the hopes of obtaining their jobs; few indeed could escape suspicion, few knew who to personal confiden end of 1938, the Great Terror was reined in. Yezhov was purged and suffered the fate of many of his victims. The Soviet Union under Stalin remained an extremely repressive state, and millions were incarcerated in labour camps until shortly after

33. Tucker, Stalin in Power, p 271. See also Hélène Carrère Stalin: Order Through Terror (Harlow, 1981), p 45.

34. JV Stalin, in Party Work and Measures for Liquidating Trotskyite and Other Double- Works, Volume 14 (London, 1978), pp 241-73.

35. Conquest, The Great Terror, passim.

6

th.36

However, the drawing down of the Great Terror did not mean the end of extreme coercion as a means of governance in the Soviet Union, and the totalitarian Stalin staged a vicious assault upon the Leningrad party leadership, and it is legitimate to consider that his sharp criticisms of the national party leaders and his anti-Semitic measures of the early 1950s were preliminaries for a new round of mass purges.37 One cannot be sure that Stalin would not have tried to repeat the Great Terror had his death not intervened.

Полл> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

Paul Flewers

Stalin and the Great Terror Politics and Personality in Soviet History

Abstract

This article starts by investigating how the Moscow Trials and the broader Great Terror of the late 1930s were seen outwith the Soviet Union at the time. It then investigates how contemporary and subsequent observers have attempted to explain them, as they viewed them variously as a logical result of Bolshevik theory and practice, rooted in the development of Soviet society, the product of Stalins personal predilections, and an attempt by Stalin to deal with the problems that he faced both personally and politically during the 1930s. It concludes that the staging of the trials and the launching of the terror can be explained by an understanding of both the peculiar nature of the Stalinist socio-economic formation and Stalins particular personal characteristics, and that had Stalin been removed from his post as General Secretary at the Seventeenth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1934, it is extremely unlikely that the Great Terror would have occurred.

Key words Moscow Trials, Stalinism, Soviet Union, state terror.

Note on the author Paul Flewers is a socialist historian and a member of the Editorial Boards of New Interventions and Revolutionary History. His book The New Civili -1941, was recently published by Francis Boutle.

***

Seventy years ago this year, in March 1938, the veteran Bolshevik revolutionaries Nikolai Bukharin, Nikolai Krestinsky, Christian Rakovsky, Aleksei Rykov and Sta r secret police chief Genrikh Yagoda sat with 16 other defendants in Charged with a variety of heinous crimes and having been subjected to months of harsh treatment at the hands of the secret police interrogators, they were harangued by Vyshinsky, found guilty, and sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment, which amounted to the same thing. This was the third of a series of major show trials, the first of which, somewhat ironically, had been held under the auspices of Yagoda. The first was held in August 1936, and resulted in Grigori Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and 14 other Old Bolsheviks being sentenced to death. The second, held in January 1937, resulted in Karl Radek, Yuri Piatakov and 15 others being sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment. Like a three-ring circus, each trial was more flamboyant than its predecessor, with increasingly lurid accusations and confessions about the defendants forming anti-Soviet terrorist groups and for years collaborating with foreign powers and the exiled Trotsky and engaging in terror and sabotage in order to overthrow the Soviet regime and re-establish capitalism, and at the third trial ultimately backdated almost to the October Revolution itself.

These three grotesque show trials were merely the public face of a far deeper

1

and broader reign of repression. In between the second and third trials, in June 1937, the Soviet government announced that several senior military leaders, including Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, had been found guilty of treason, and had been executed. All the while, the Soviet press was providing long lists of names of officials who had been purged for their alleged involvement in heinous activities against the Soviet state, and plenty more were disappearing without notice. The number of people officially executed during 1937-38 stands at 681 692, although this figure has been considered an underestimate, and it has been estimated that during that time squad, physical maltreatment or massive over- 1939, there were 2.9 million prisoners in labour camps and prisons.1 This was the time of the Great Terror.

I: Looking at the Great Terror

At the time, the Moscow Trials and the concurrent reign of terror divided opinion in Britain. The adherents of the pro-Soviet lobby the official communist movement and its fellow-travelling allies reasons for the purges and hailed the show trials as a victory for the socialist state over the forces of counter-revolution,2 or, if they did have a few qualms, very much gave the Soviet regime the benefit of the doubt.3 Some commentators, most notably the left-wing intellectuals Harold Laski and Kingsley Martin, wobbled alarmingly between believ government which were objectively counter- level of repression and lack of free expression in the Soviet Union.4 Some people, whilst unequivocally discounting the allegations and confessions about desiring to return to capitalism, plotting sabotage and collaborating with foreign powers, nonetheless considered that there was a possibility of Trotsky conspiring in a political manner with the defendants with the aim of unseating Stalin, as this was the only way in which opposition to him could be manifested in a country where there was no opportunity for open political discourse.5 There were a few strongly anti- communist observers who accepted the core allegations against the Soviet military leaders, if not all the details,6 presumably on the basis that viewing them as

1. Robert Service, A History Twentieth-Century Russia (London, 1997), pp 222-24.

2. See, for example, Dudley Collard, Soviet Justice and the Trial of Radek and Others (London, 1937); William and Zelda Coates, From Tsardom to the Stalin Constitution (London, 1938); JR Campbell,

Soviet Policy and Its Critics (London, 1939).

3. Sidney and Beatrice Webb accepted the trials as genuine, but with little of the sense of

triumphalism demonstrated by many other pro-Soviet people. Their mammoth treatise accepted that there were considerable restrictions upon independent thinking, and that the powers were dangerously wide, but, all in all, average thoroughly believes that it is to the vigilance of the GPU that is due the continued existence of the Soviet state, which would otherwise have been by internal and external enemies (S and B Webb, Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation (London, 1937), p 586). So alright then.

4. Harold Laski, Record of New Statesman, 30 July 1938, p 192; Kingsley Martin, Moscow New Statesman, 5 September 1936, pp 307-08.

5. John Maynard, on the Trotskyist Political Quarterly, Volume 8, no 3, July 1937, p 94; HC Foxcroft, Revolution Quarterly Review, January 1938, p 9; Peter Horn, Lesson of the Moscow Controversy, March 1937, p 104.

6. Henry Wickham Steed, Anti-Bolshevist Fr International Affairs, Volume 16, no 2, March 1937, p 185; Robert Seton-Watson, Britain and the Dictators: A Survey of Postwar British

2

fraudulent undermined the legitimacy of their call for an Anglo-Soviet bloc against the threat posed by Nazi Germany.

Most observers at the time, however, were horrified by the purges and the trials, and a wide range of commentators in Britain found the accusations and confessions just too fantastic to be taken seriously. The Spectator averred that the evi7 whilst the Economist the third one.8 The veteran socialist Henry Brailsford declared that he had been very sceptical about Soviet justice ever since the Menshevik Trial in 1931, at which it was stated that the Menshevik leader Rafael Abramovich had been plotting in Moscow on the very day when he was actually with Brailsford and other socialists in Brussels.9 It was pointed out that the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen, at which Sedov in 1932, had in fact been demolished in 1917 and not rebuilt.10 EH Carr sarcastically wrote off both DN Pritt, the British apologist for the trials, and the trials 11 Writing pungently about the second trial, but with equal relevance to all three, the academic Goronwy Rees, who until then had held a fairly positive attitude towards the Soviet Union, pointed out that the whole case rested upon confessions lacking documentary evidence, that absurdities, contradictions and even impossibilities in the evidence were not challenged, that exact dates were never given, and that confessions were directed by leading questions. He then asked his erstwhile colleagues of the pro-Soviet lobby if this could be anything other than the justice of a police state.12 George Soloveytchik, a Russian liberal exile, drew out the logic of the trials:

After all, there are only two possibilities: either all these men are guilty, in

build élite which is now being exterminated by its chief is the worst kind of scum the world has yet produced, or else the allegations are not true, and then the indictment of this regime which is compelled to invent such ghastly charges is even more devastating.13

Some people, including George Orwell and the radical novelist Nigel Balchin, found the spectacle of the trials so bizarre that they ridiculed them in a couple of satirical sketches that combined delightful whimsy with devastatingly sharp insights.14

The Stalinists countered their critics, and they did, on the face of it, have a reasonable case. Why, they asked, with the Soviet Union doing so well, would Stalin

Policy (Cambridge, 1938), pp 134-36.

7. of the Spectator, 29 January 1937, pp 153-54.

8. of the Economist, 5 March 1938, p 494.

9. HN Brailsford, New Statesman, 31 July 1937, p 181.

10. Friedrich Adler, The Witchcraft Trial in Moscow (London, 1936), pp 15-16.

11. EH Carr, International Affairs, Volume 16, no 2, March 1937, p 311.

12. Goronwy Rees, Twilight of Spectator, 21 May 1937, p 956.

13. George Soloveytchik, Contemporary Review, February 1938, p 153.

14. George Orwell, New English Weekly, 9 June 1938, p 169; Nigel Balchin,

or Night and Day, 19 August 1937, p 3. article was republished in New Interventions, Volume 11, no 4.

3

stage a series of fake trials, what possible purpose could it have?15 Did not the defendants confess their guilt, unlike Georgi Dimitrov at the Reichstag Fire Trial?16 Observers repelled by the trials racked their brains attempting to comprehend why they had taken place, and why the defendants had confessed. Stalin was considered p.17 Some relied upon clichés, with, for example, the staunch right-winger Charles Petrie proclaiming sagely that the trials proved the adage that revolutions end up devouring their own children,18 an observation that does little to explain the complex issues of power in post-revolutionary societies, whilst a right-wing - 19

The rather obvious point was made that the trials indicated a profound crisis within the Soviet regime.20 But what was behind the crisis? One theory held that Stalin was staging the trials in order to shift the blame for economic mismanagement from his regime onto scapegoats. After outlining many instances of major malfunctions, poor management and general incompetence, the Moscow correspondent of the Economist of gross inefficiency need not cast discredit upon central planning, which, without some such explanation, migh were accepted as genuine by most Soviet citizens, could act as a conductor, using the defendants as a focus for popular discontent that might otherwise be directed against the government.21 CLR James considered that Stalin was attempting to crush a burgeoning wave of opposition.22 He added that Stalin was attempting to pre-empt anyone within the party-state apparatus who intended him to meet the same fate as Robespierre, and that by allowing workers to be promoted into jobs vacated by purged man 23 Many observers, including Winston Churchill and EH Carr, maintained that Stalin was clearing out the Old Bolsheviks who maintained a commitment to the cause of world revolution,24 and others felt that he was purging the bureaucracy in order to reinforce his position by forestalling the rise of any potential opposition, and clearing out all but the most servile of his retinue.25

s denunciation of Stalin in 1956, the

15. Campbell, Soviet Policy and Its Critics, pp 248-49.

16. John Strachey, of the Month: The Soviet Tria Left News, March 1937, 274.

17. of the National Review, July 1937, pp 8-9.

18. Charles Petrie, English Review, October 1936, p 361.

19. of the National Review, April 1938, p 433.

20. of the Wee Economist, 22 August 1936, p 345.

21. Economist, 27 February 1937, p 466.

22. CLR James, World Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International (London, 1937), p

367.

23. CLR James, Controversy, October 1937, p 8.

24. Winston S Churchill, Step by Step, 1936-1939 (London, 1939), pp 60-61; EH Carr, Russia (London,

1937), p 6; at the Contemporary Review, December 1937, pp 690-91; AS Elwell-Sutton, Russian New English Weekly, 12 January 1938, pp 268-89; Franz Borkenau, World Communism: A History of the Communist International (London, 1939), p 423.

25. of the Economist, 25 December 1937, p 634; Nicholas de Basily, Russia Under Soviet Rule: Twenty Years of Bolshevik Experiment (London, 1938), p 252; Frederick Voigt, Unto Caesar (London, 1938), p 253.

4

extensive research work carried out in the West, and the vast array of documentary evidence available for study in the Soviet archives, the Great Terror is accepted as an historical fact. Only a few disturbed individuals, kennelled away in the pro-Stalin corner of the left, now promote an unblemished picture of the Stalin era, or claim that the Moscow Trials represented anything other than a cruel parody of a legal process.26 The extent of the Terror has been extensively researched, although the precise number of victims remains a subject of debate. The cruel methods used by nfessions are public knowledge. The discussion today is largely centred upon questions of interpretation, and the same questions that puzzled observers seven decades ago are often repeated: why did the terror take place, and what were the driving forces behind it?

Many standard accounts of the Terror consider that there were several crucial formative factors. Firstly, there was the emergence of opposition amongst previously trusted members of the Soviet Communist Party leadership during the First Five- w official Maremian Riutin be executed after he was discovered to have written a detailed oppositional programme that called for the removal of Stalin from his post of General Secretary.27 Secondly, there was the implicit snubbing of Stalin at the Seventeenth Party Congress in 1934, where, depend 28 and where there was private talk (which no doubt swiftly reached Stalin) of ary. Thirdly, Kirov was promoting a call for a more liberal party regime, reconciliation with former oppositionists, and a reduction in state coercion.29 Fourthly, there was the subsequent assassination of Kirov on 1 December 1934, for which many commentators claim that Stalin was responsible,30 or that, if there is no direct proof that he was, of which he took full political advantage.31 Ronald Hingley summed up for removing all other rivals, actual and potential, numbering several millions, in the Great Terror of 1937-32

26. Two works demonstrating adage that paper will take anything written on it are Kenneth Cameron, Stalin: Man of Contradiction (Stevenage, 1988), and Harpal Brar, Perestroika: The Complete Collapse of Revisionism (London, 1992), which both consider that the Moscow Trials were fair, and deny the existence of the Ukrainian famine and the Gulag.

27. Ronald Hingley claimed that call to shoot Riutin was to blish a valuable prece and give him right to consign to death without question, let or hindrance, any communist or expelled communist, from the most senior (Ronald Hingley, Joseph Stalin: Man and Legend (London, 1974), p 218).

28. Robert Tucker gave the lower figure, Dmitri Volkogonov the higher one. See Robert Tucker, Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928-1941 (New York, 1992), p 260; Dmitri Volkogonov, Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy (London, 1991), p 200.

29. oris Nicolaevsky, Power and the Soviet Élite (London, 1966), pp 29ff.

30. Particularly Tucker, Stalin in Power, pp 275-76; Robert Conquest, Stalin and the Kirov Murder (London, 1989), passim; Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (Oxford, 1989), p 345.

31. Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (London, 2004), p 315; Donald Rayfield, Stalin and His Henchmen: An Authoritative Portrait of a Tyrant and Those Who Served Him (London, 2004), p 240.

32. Hingley, Joseph Stalin, p 236. Robert Conquest saw the Kirov affair as the on the way to (Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment (London, 1990), p 51).

5

The Great Terror followed the tremendous increase in state coercion and con ctivisation schemes that started in 1929 with the First Five-Year Plan. There had been something of a lull in the level of state repression and official hysteria after the chaotic events of the initial Five-Year Plan had calmed down, and there were widespread hopes that the worst of the upheavals were over. The public image of the Seventeenth Congress was that of party unity having superseded the deep divisions evident at earlier national gatherings. This, however, was very much a false dawn, as a new bout of state- assassi time; indeed, as early as the latter half of 1932.33

ount, the Great Terror itself started with the trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev in August 1936, with many preparatory that the GPU was running four years behind in revealing malcontents, and its head Genrikh Yagoda was replaced by Nikolai Yezhov. The trial of Radek and Piatakov took place in January 1937, and in February-March of that year the Soviet ttee met with the simple agenda of dealing with the matter of Bukharin and Rykov; that is, setting them up for persecution. The centre - Work and Measures for Liquidating Trotskyite and other Double- General Secretary warned that the more successful the Soviet Union became, the enemies; and that members of the Soviet Communist Party were most lax in their appreciation of the dangers posed to the Soviet Union.34 It was a clear signal for the implementation of widespread terror, and by mid-1937, with a purge of the secret police, Stalin was in full control of the machinery of mass repression.35

The period from mid-1937 to late 1938, the Yezhovshchina, was the full-blown Terror, marked most publicly by the grotesque third Moscow Trial in March 1938. The Terror affected practically every corner of the Soviet regime. The middle cadre, by then mostly loyal to the general Stalinist line, was purged, often with the lower echelons whipping up a witch-hunt atmosphere against them. The military leadership and industrial management structures were particularly badly hit, as were party leaderships in the non-Russian republics, but no government department escaped, and soon nobody at all was safe as the dragnet descended to the rank-and-file worker and peasant. Brutal interrogation resulted in those arrested implicating others, some people denounced others for personal revenge or in the hopes of obtaining their jobs; few indeed could escape suspicion, few knew who to personal confiden end of 1938, the Great Terror was reined in. Yezhov was purged and suffered the fate of many of his victims. The Soviet Union under Stalin remained an extremely repressive state, and millions were incarcerated in labour camps until shortly after

33. Tucker, Stalin in Power, p 271. See also Hélène Carrère Stalin: Order Through Terror (Harlow, 1981), p 45.

34. JV Stalin, in Party Work and Measures for Liquidating Trotskyite and Other Double- Works, Volume 14 (London, 1978), pp 241-73.

35. Conquest, The Great Terror, passim.

6

th.36

However, the drawing down of the Great Terror did not mean the end of extreme coercion as a means of governance in the Soviet Union, and the totalitarian Stalin staged a vicious assault upon the Leningrad party leadership, and it is legitimate to consider that his sharp criticisms of the national party leaders and his anti-Semitic measures of the early 1950s were preliminaries for a new round of mass purges.37 One cannot be sure that Stalin would not have tried to repeat the Great Terror had his death not intervened.

VAS63:

предупреждение (+1) по категории «Обширная цитата на иностранном языке без перевода [п.16]»

Полл>> Это новая, мне не встречавшаяся версия истории России, Украины и СССР.

Полл>> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл>> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

bureaucratic state based upon terror did not come as a surprise to some. Socialism, they claimed, would lead to tyranny, as sure as night follows day. The fear of totalitarianism preceded both the society and the term. In his polemic against Marx, the anarchist Bakunin claimed that any society run under the banner of Marxism scientific intelligence, the most aristocratic, despotic and end scientists and 38 lleled by certain radicals, Machajski concluded that socialism represented the seizure of power by the intelligentsia, and the emergence of a new form of exploiting society.39 Oppo and brigade us into a kind of barrack- a automata moved by the all-absorbing and all- 40

For conservatives and libertarians alike, the rise of Stalinism merely confirmed their preconceptions. Many of them have seen Leninism as incipiently or actually totalitarian in outlook, and viewed the Terror as the inevitable consequence of that school of thought. Some observers have claimed that the roots of this totalitarian trend can be found amongst the various strands of thought that emerged during and after the Enlightenment. Robin Blick, a libertarian socialist, considered that Lenin, whilst claiming to stand in the Marxist tradition, harked back to Robespierre, Blanqui and the Russian populists, who, by claiming to be the infallible leadership of the revolutionary masses, adhered to an élitist stance towards them.41 The back to pre-Marxian philosophers such as the

36. Conquest, The Great Terror, passim.

37. Robert Conquest, Stalin: Breaker of Nations (London, 1993), pp 304ff; Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A

Political Biography (London, 1966), pp 602ff.

38. M Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (London, 1984), p 38.

39. See M Shatz, Jan aw Machajski: A Radical Critic of the Russian Intelligentsia and Socialism

(Pittsburg, 1989), passim.

40. Labour and Luxury: A Reply to (London, 1895), p 107.

41. Robin Blick, The Seeds of Evil: Lenin and the Origins of Bolshevik Élitism (London, 1995), pp 36-53.

7

Encyclopedists of the eighteenth century.42

Some observers have sought the roots of Stalinist totalitarianism in the peculiar

historical development of Russia. The conservative historian Adam Ulam stated that a vanguard party a hierarchical organisation which implied par was heavily influenced by the experience of the Decembrists and the populists, who were forced to work in clandestinity because of the repressive nature of Tsarism. He considered that the response of Nicholas I to the Decembrist uprising ething more approximating the modern polic institu move 43 ms like class war, class justice, en which individual guilt or innocence was the consequence not of facts but of political and social imper 44

Merle Fainsod posited the bas revolutionary party. He noted various fac ntolerance of disagreement and co Although Lenin recognised that differences of opinion in the party were inevitable, and rarely implemented the last resort of expulsion from the party, he left precedents that permitted the totalitarianisation of the party to go ahead after his death.45

Some left-wing critics of Bolshevism have also rooted the repressive nature of

class, and in the consequences of attempting to move towards building socialism in a on of a clandestine party led to his recommending a powerful dictatorial leadership that would demand that the working class subordinate itself to it. This would lead to the outlook, the inability of the party to work with other socialist currents, and the viewing of them as enemies, against whom any manoeuvres were acceptable. The rule by terror, which was greatly exacerbated by their utopian attempts to build a socialist society in a backward country.46

These concepts of the inevitability of Stalinist totalitarianism have been strongly challenged by various commentators who have taken a radically different

42. Martin Malia, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917-1991 (New York, 1994), pp 186, 225.

43. Adam Ulam, Lenin and the Bolsheviks (London, 1973), pp 37-38, 236-37, 247.

44. Adam Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (New York, 1973), p 413.

45. Merle Fainsod, How Russia is Ruled (Cambridge, 1953), pp 47, 138.

46. Karl Kautsky, Social Democracy Versus Communism (New York, 1946), pp 48-66.

8

standpoint. Not merely have they placed far more emphasis upon conditions that existed and events that took place after the October Revolution to explain the rise of Stalinism, but have also argued that Stalinism was not the logical outcome of either Bolshevism47 or the events during the early years of the Soviet regime.48

In an analysis no doubt familiar to readers of this magazine, Trotsky considered that the isolation of the Soviet republic in a backward, war-ravaged country meant that the building of a fully socialist society was impossible within its boundaries, although certain moves could be made in a socialist direction, and that the experience of the Civil War and its aftermath, with the exhaustion of the working class and the absorption of the Communist Party into the state apparatus, resulted in the rise of the Soviet party-state apparatus during the 1920s into a privileged stratum of society and eventually a ruling élite, which was personified by Stalin.49 However, Trotsky also pointed to characteristics of Russian society prior to 1917 that impacted upon Bolshevism and which subsequently assisted the rise of Stalinism. He noted that in a country with a backward and scattered working class, and in which politics were clandestine, a cen over the working class. Stalin was not just a classic case of such a person:

Devoid of personal qualifications for directly influencing the masses, he

his blind loyalty to the party machine was to develop with extraordinary force; the committee man became the super- General Secretary, the very personification of the bureaucracy and its peerless leader.50

Nonetheless, this was not by any means the main reason why Stalin ended up where he did. Post-1917 events, and particularly the Civil War, were of key importance:

The three years of Civil War laid an indelible impress on the Soviet government itself by virtue of the fact that very many of the administrators, a considerable layer of them, had become accustomed to command and demand unconditional submission to their order is no doubt that Stalin, like many others, was moulded by the environment and circumstances of the Civil War, along with the entire group that later helped him to establish his per 51

47. For a thorough debunking of the usual myths surrounding Lenin and the Bolshevik party, see Lars T Lih, Lenin Rediscovered: Is To Be In Context (Leiden, 2005).

48. Hannah Arendt claimed that whilst Bolshevism was its one-party rule not necessarily have led to She saw Stalin introducing a totalitarian form of rule as a policy option, in order to destroy the existing social classes (the peasantry, working class and bureaucracy), and fabricate an atomised and structureless In other words, socio-economic policies were predetermined by his desire for a totalitarian society (Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (London, 1986), pp 319-22).

49. This is most comprehensively elaborated in LD Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed: What Is the Soviet Union and Where Is It Going? (London, 1937).

50. LD Trotsky, Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and his Influence (New York, 1967), p 61.

51. Trotsky, Stalin, pp 384-85.

9

ncy during the first decade or so of the Soviet regime was a narrow quest for personal power, or even that he was conscious e was unaware of the social significance privileged caste welded together by the bond of honour among thieves, by their common interest as privileged exploiters of the whole body politic, and by their ever- 52 Furthermore:

If Stalin could have foreseen at the very beginning where his fight against Trotskyism would lead, he undoubtedly would have stopped short, in spite of the prospect of victory over all his opponents. But he did not foresee anything.53

potential in full, demonstrates that Trotsky considered that even with the decline of the revolutionary forces in the Soviet Union during the early 1920s, the rise of Stalinism in the specific manner in which it arose was not inevitable.

In some respects, the analysis elaborated by the dissident Soviet Marxist Roy Medvedev followed that of Trotsky, in that he considere power was facilitated by certain historical features of Russian society, and by decisions made and practices followed by the Bolsheviks once they were in power and which were forced upon them by the onerous objective conditions that confronted them.

Medvedev considered that the extremely difficult position of the Soviet republic during the Civil War forced the Bolsheviks to establish a political monopoly and the strict centralisation of society, but felt that these were seriously problematic, s prolonga uch these factors were temporary measures to enable the regime to survive a very and terror create not only habits but also institutions, which are even harder to nistration such as the former Men those who were not seduced by the privileges and power of authority found difficulty in moving from the authoritarian atmosphere of Civil War leadership into a frame of mind more suited to complex educational work. The low level of culture and education and weak democratic traditions in Russia, along with the exhaustion of the working class and the general disruption caused by the Civil War which led to the decline of popular institutions that could exert control over the regime, did much to assist the rise of the Communist Party over the working class and society in general. Such were the objective and subjective factors that permitted the rise of Stalinism.54

There is also the question, raised by some commentators, of the main political

52. Trotsky, Stalin, p 386.

53. Trotsky, Stalin, p 393.

54. Medvedev, Let History Judge, pp 614-720.

10

influence upon the Bolsheviks; that is to say, the paternalistic Marxism of the Second

Bolsheviks were ultimately unable to break from it, as can be seen in the measures that they implemented which resulted in the ascendancy of the Soviet Communist Party above the working class.55

Trotsky and those who follow his analysis considered that the programme of the Left Opposition provided a superior alternative to that promoted by Stalin. Medvedev, along with Moshe Lewin and Stephen Cohen, considered that the programme evolved by Bukharin would have provided another better alternative to Stalinism.56 These positive sentiments stand in contrast to the critics of Bolshevism cited above who considered that Stalinism was the ineluctable consequence of the Bolshe

III: Why the Terror?

Commentators have largely agreed that one reason why Stalin embarked upon his campaign of terror was in order to forestall the rise of any potential political opposition. Looking at the assault upon the higher echelons of the Communist Party, potentiali several alter 57 Alan Bullock stated that Stalin had come to view i the late 1920s, but who still considered themselves partners rather than minions and held their own opinions.58 Medvedev added that during the early 1930s there was a ositionists.59 Similarly, the assault on the military has been seen as destroying a focus of potential opposition;60 indeed, Deutscher went so far as to declare that Tukhachevsky and his colleagues were actually engaged in a plot to overthrow Stalin,61 although this is a view that has been largely discounted.62

The three Moscow Trials have been regarded as a means of destroying the very character and integrity of potential oppositionists. Deutscher stated that had the defendants been presented as being merely politically opposed to Stalin, they may u looked upon, especially by the young and uninformed generation, as the saviour of 63 The show trials have also been seen as a means of providing a

55. o Red Petrograd: Revolution in the Factories 1917-18 (Cambridge, 1986), pp 259ff.

56. Medvedev, Let History Judge, pp 203-04; Moshe Lewin, Political Undercurrents in Soviet Economic Debates: From Bukharin to the Modern Reformers (London, 1975), passim; Stephen Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888-1938 (Oxford, 1980), passim.

57. Deutscher, Stalin, p 372.

58. Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (London, 1993), p 386. See also Malia, The Soviet

Tragedy, pp 250ff.

59. Medvedev, Let History Judge, p 328.

60. Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Permanent Purge: Politics in Soviet Totalitarianism (Cambridge, 1956),

p 76.

61. Deutscher, Stalin, pp 375-76.

62. For example, Conquest, The Great Terror, p 186.

63. Deutscher, Stalin, p 374. See also Bullock, Hitler and Stalin, p 547.

11

i to launch. William Chase noted that by pointing to a threat posed by not - them out, and the local secret police would obtain confessions that proved their 64

ac emerge e in the Soviet Union,65 points accepted by other writers.66 was unusual as it gave little significance to the events at the Seventeenth Party Congress, and placed considerably more emphasis upon discontent within the country as a whole. He considered that after the fraught experience of the First Five- living and working in worsened conditions; intellectuals, experts and managers chafing against harassment; religious and national groups angry at their treatment; defeated oppositionists and former members of outlawed political parties bridling c enty of human material across the USSR which could, if conditions changed, be diverted into a coup against his 67 However, other commentators have downplayed the actual opposition that Stalin faced. Deutscher, for example, considered that although 68

The reasons for the frightful dimensions of the Terror have been probed. Deutscher recognised that once put into motion, such repression would of necessity become pervasive and self-perpetuating:

He [Stalin] had set out to destroy the men capable of forming an alternative government. But each of those men had behind him long years of service, in the course of which he had trained and promoted administrators and officers and made many friends. Stalin could not be sure that avengers of his victims would not rise from the ranks of the followers. Having destroyed the first team of potential leaders of an alternative government, he could not spare the second, the third, the

64. oscow Show Trials and the Construction of Mortal Stalin: A New History (Cambridge, 2005), p 247.

65. Medvedev, Let History Judge, pp 273, 389.

66. Volkogonov, Stalin, pp 209, 212. Roberta Manning considered that the Terror was in response

to severe economic difficulties emerging from the Five-Year Plans, and in turn exacerbated - Getty and RT Manning, Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives (Cambridge, 1993), pp 116-41. See also Alec Nove, Stalinism and After (London, 1981), p 61.

67. Service, Stalin, pp 313-16.

68. Deutscher, Stalin, p 372.

12

fourth, and the nth teams.69

In short, once the Terror started, its possible extent could not be determined, as it would take on a dynamic of its own so long as the arrests, interrogations and denunciations mounted, and so long as Stalin and his closest allies were happy to sign the death warrants and refuse to bring it to a halt.

So why was the Great Terror brought to a close? Conquest argued that the Terror, which hit practically every sector of Soviet society, was wound down without inflicting irreparable damage on the country: the secret police could not ignore someone against whom allegations had been made; and when he or she rate arrests were going, practically all the urban population would have been 70 Service stated that Stalin and his clique had come

The blood- period of intense international tension. The arrest of the economic administrators in the peop The destruction of cadres in party, trade unions and local government undermined administrative coordination. This extreme destabilisation endan career would be at an end.71

Nevertheless, the very extent of the repression did bring about what, according to

remould the Soviet élite so that it would be in his image and firmly under his personal control; the creation of a regime that represented a radical break from its predecessor, whilst still promoting Stalin as the sole legitimate heir of the October Revolution.72 Hingley drew out the functional rationale of the Terror that existed beneath all the chaos and destruction:

Driven by an inner urge to make certainty doubly certain, and to maximise dominion which had long seemed total to all save himself, while insuring against all possible threats to his person and system, the dictator could never rest easy so long as there remained, in the length and breadth of his realm, any established and cohesive institution however thoroughly Stalinised which might conceivably turn against its creator. Reconstructing, refreshing and reforming successive hierarchies in order to destroy existing vested interests, he found himself constantly impelled to turn and rend each newly arising organisation even as it appeared to attain some degree of cohesion. From the Politbureau down to the individual family all human associations must be prevented from

69. Deutscher, Stalin, p 377.

70. Conquest, The Great Terror, pp 289, 433.

71. Service, A History Twentieth-Century Russia, pp 225-26.

72. Bullock, Hitler and Stalin, pp 550-01; Conquest, The Great Terror, pp 445ff; Tucker, Stalin in

Power, pp 319ff, 526ff.

13

acquiring stability and esprit de corps.73

During the 1980s, the traditional view of the Great Terror started to come under sustained criticism from revisionist historians. The most noted of this school, J Arch Getty, considered that the whole process of terror in the 1930s was far less coordinated than normally accepted, and he reject view of the purges, and the idea that Stalin had any terroristic grand design. He viewed the Soviet leadership around Stalin as a fractious group which encompassed a wide range of ideas on many issues, and not as a monolithic bunch of yes-men. In many cases, he declared, Stalin took a more moderate line than, say, Molotov on industrialisation, or arbitrated between opposing views. He considered that the party- Terror it 74

Getty shifted the responsibility for the Terror to some degree from Stalin. Although Stalin took ultimate responsibility, not least in unleashing Yezhov, a deter rty- id-1937. The Yezhovshchina had -leadership, anti- the lower echelons of the party to attack their superiors, but because criticism democratising wind bureaucratic factions and interest groups settling old scores.75 And looking at the results of the Terror, unlike the totalitarian school, which has customarily seen the purges m 76 Getty stated that the party after the Terror was no better behaved and obedient than before. There was a shortage of trained and educated cadres, and, because of the way that rank-and-file members had acted against their superiors, there was no way of guaranteeing their obedience to party secretaries in the future.77

Полл>> Можно с ней ознакомится?

Полл>> Прошу ссылку на научный труд с данной версией истории.

bureaucratic state based upon terror did not come as a surprise to some. Socialism, they claimed, would lead to tyranny, as sure as night follows day. The fear of totalitarianism preceded both the society and the term. In his polemic against Marx, the anarchist Bakunin claimed that any society run under the banner of Marxism scientific intelligence, the most aristocratic, despotic and end scientists and 38 lleled by certain radicals, Machajski concluded that socialism represented the seizure of power by the intelligentsia, and the emergence of a new form of exploiting society.39 Oppo and brigade us into a kind of barrack- a automata moved by the all-absorbing and all- 40

For conservatives and libertarians alike, the rise of Stalinism merely confirmed their preconceptions. Many of them have seen Leninism as incipiently or actually totalitarian in outlook, and viewed the Terror as the inevitable consequence of that school of thought. Some observers have claimed that the roots of this totalitarian trend can be found amongst the various strands of thought that emerged during and after the Enlightenment. Robin Blick, a libertarian socialist, considered that Lenin, whilst claiming to stand in the Marxist tradition, harked back to Robespierre, Blanqui and the Russian populists, who, by claiming to be the infallible leadership of the revolutionary masses, adhered to an élitist stance towards them.41 The back to pre-Marxian philosophers such as the

36. Conquest, The Great Terror, passim.

37. Robert Conquest, Stalin: Breaker of Nations (London, 1993), pp 304ff; Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A

Political Biography (London, 1966), pp 602ff.

38. M Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (London, 1984), p 38.

39. See M Shatz, Jan aw Machajski: A Radical Critic of the Russian Intelligentsia and Socialism

(Pittsburg, 1989), passim.

40. Labour and Luxury: A Reply to (London, 1895), p 107.

41. Robin Blick, The Seeds of Evil: Lenin and the Origins of Bolshevik Élitism (London, 1995), pp 36-53.

7

Encyclopedists of the eighteenth century.42

Some observers have sought the roots of Stalinist totalitarianism in the peculiar

historical development of Russia. The conservative historian Adam Ulam stated that a vanguard party a hierarchical organisation which implied par was heavily influenced by the experience of the Decembrists and the populists, who were forced to work in clandestinity because of the repressive nature of Tsarism. He considered that the response of Nicholas I to the Decembrist uprising ething more approximating the modern polic institu move 43 ms like class war, class justice, en which individual guilt or innocence was the consequence not of facts but of political and social imper 44

Merle Fainsod posited the bas revolutionary party. He noted various fac ntolerance of disagreement and co Although Lenin recognised that differences of opinion in the party were inevitable, and rarely implemented the last resort of expulsion from the party, he left precedents that permitted the totalitarianisation of the party to go ahead after his death.45

Some left-wing critics of Bolshevism have also rooted the repressive nature of

class, and in the consequences of attempting to move towards building socialism in a on of a clandestine party led to his recommending a powerful dictatorial leadership that would demand that the working class subordinate itself to it. This would lead to the outlook, the inability of the party to work with other socialist currents, and the viewing of them as enemies, against whom any manoeuvres were acceptable. The rule by terror, which was greatly exacerbated by their utopian attempts to build a socialist society in a backward country.46

These concepts of the inevitability of Stalinist totalitarianism have been strongly challenged by various commentators who have taken a radically different

42. Martin Malia, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917-1991 (New York, 1994), pp 186, 225.

43. Adam Ulam, Lenin and the Bolsheviks (London, 1973), pp 37-38, 236-37, 247.

44. Adam Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (New York, 1973), p 413.

45. Merle Fainsod, How Russia is Ruled (Cambridge, 1953), pp 47, 138.

46. Karl Kautsky, Social Democracy Versus Communism (New York, 1946), pp 48-66.

8

standpoint. Not merely have they placed far more emphasis upon conditions that existed and events that took place after the October Revolution to explain the rise of Stalinism, but have also argued that Stalinism was not the logical outcome of either Bolshevism47 or the events during the early years of the Soviet regime.48

In an analysis no doubt familiar to readers of this magazine, Trotsky considered that the isolation of the Soviet republic in a backward, war-ravaged country meant that the building of a fully socialist society was impossible within its boundaries, although certain moves could be made in a socialist direction, and that the experience of the Civil War and its aftermath, with the exhaustion of the working class and the absorption of the Communist Party into the state apparatus, resulted in the rise of the Soviet party-state apparatus during the 1920s into a privileged stratum of society and eventually a ruling élite, which was personified by Stalin.49 However, Trotsky also pointed to characteristics of Russian society prior to 1917 that impacted upon Bolshevism and which subsequently assisted the rise of Stalinism. He noted that in a country with a backward and scattered working class, and in which politics were clandestine, a cen over the working class. Stalin was not just a classic case of such a person:

Devoid of personal qualifications for directly influencing the masses, he

his blind loyalty to the party machine was to develop with extraordinary force; the committee man became the super- General Secretary, the very personification of the bureaucracy and its peerless leader.50

Nonetheless, this was not by any means the main reason why Stalin ended up where he did. Post-1917 events, and particularly the Civil War, were of key importance:

The three years of Civil War laid an indelible impress on the Soviet government itself by virtue of the fact that very many of the administrators, a considerable layer of them, had become accustomed to command and demand unconditional submission to their order is no doubt that Stalin, like many others, was moulded by the environment and circumstances of the Civil War, along with the entire group that later helped him to establish his per 51

47. For a thorough debunking of the usual myths surrounding Lenin and the Bolshevik party, see Lars T Lih, Lenin Rediscovered: Is To Be In Context (Leiden, 2005).